Centers:

of Place, Attention. and Attraction

(Drawing from Our Own True Nature - Part 3)

Place is the first of all beings, since everything that exists is in a place and

cannot exist without a place.

- Archytas ‘Commentary on Aristotle's Categories’

A place for everything, and everything in its place

"The question is not what you look at —

but how you look and whether you see." - Thoreau

There is a center to all this

and it’s all in a place

So, how do we do this - draw from our own true nature?

It begins in a place,

in a way of being in a place,

and a way of being in place there (1).

Come, follow me out the door and into the woods behind my house.

It is a warm, sun shining mid October afternoon as we step off the dirt road and cross the verge of drying grass rustling beneath our shoes. Asters, the palest of blue now, mingle among the bending stems. We push through the thicket of Rhododendron, push long trailing branches aside, and step from the outside of warm sunlight on our face into the inside of cool dancing shadows of deep umbers and dark greens. The moist aroma of humus envelopes us, and we feel we have stepped from the outside of something into the inside of something else.

Scattered at our feet are pale yellow leaves Hornbeam, some of the first to fall this time of year. In this place sunlight still comes, but only splintered pieces of it, shaped like blades scattered here and there on Rhododendron leaves, shards of that whole sky we felt outside on the road. Its light still carries the blueness of a sky now far above us. Here below, it is the shadows that draw us in.

A fallen and rotting Maple tree lays here, its punky old body slowly sinking into itself, but still ample and fat enough to sit on. We sit and it is only now that the tinkle of a nearby branch of water comes to us. What is it about intimate places that often open our ears? We take off our shoes and socks, and now we feel the cool moisture that nurtures the forest floor, and so too much of the life around us here. We stand up and begin to walk, slowly and with care (2). Along with the coolness coming up through our soles, we feel the particular dry texture of a small cluster of pine needles, the slick smooth of fallen Rhododendron leaves, the crumble of pieces of bark, the tickle of a shiny black beetle scurrying out from beneath, the pillowy softening of moss. We feel where the ground softly rises to our foot, and where it comes up hard. This last tells of a trail, a path, and we follow.

Paths always go somewhere. It’s in their nature. We know this, so we look ahead to see where. It meanders and wanders away from us until it’s trace gradually disappears among what seems a meaningless tangle of Laurel, Hemlock, Oak Hickory, and countless others. We follow, and in following the trail opens up before us, and in following we follow the impress of generations of other creatures coming along this very same way, leaving their impressed pressure of passing, of goings and comings to some felt need or urge, or even curiosity.

Follow this passing of beings and see that they and we together are making a way up into a deep fold between two high ridges, along with a small gurgling stream that is tracing its own path back downward. Along its water born path stand tall sentinel Hemlocks firmly anchoring its banks, some six feet in diameter and several hundred years old. They are all dying now from a blight (3). One soft foot step after another we slowly make our way, stepping between the catastrophe of dead limbs scattered around the dying, feeling for the firmness of the trail through our soles more than looking for it.

Suddenly the bower of arching Rhododendron thicket gives way to opening woods. The land rises here and our breathing deepens. Tall trees spread out across an open slope that reaches down from the ridge, spreads out, and then gently pushes the path of the stream it into a wide curve around. Oak and Hickory reach far above. Beneath them in the vast airy understory weave spindly, wispy saplings of Holly, Sassafras, Mountain Maple, and Poplar. Standing at the edge of this open half moon shape between slope and stream, on our backs, on the nape of our necks, feel the gentle stir of air flowing up the cove with the warming day. Rat-at-tat-tat! A wood pecker startles us. Its sound fills the cove and fills ourselves. Echoes off the slopes on either side almost give us the shape of this cove (4) .This is a conversation - woodpecker calls - we listen - the hills echo - then we hear the shape of this place. We are startled because hearing is so intimate. It makes us vulnerable (5). We become a little more attentive to surprises.

Before us, the trail heads straight through this open place, as if in a hurry to reach the thicket of Laurel farther on, as if all who pass this way know to seek some security beyond. Its imprint in the soft earth makes a deep furrow in the soft earth and tells us this is a very old line of passage drawn through these woods.

We pause. At our feet notice the almond shaped tracks pressed neatly into the earth, paired two by two where a deer has stood here too and paused, just like us. All who have passed this way have and known that this is a place. It will open up all around us, and if we step into it we too will come into its center, its focal point, and be revealed.

There is a center to all this

and it’s all in attention

Walk out into the opening, feel the spaciousness spread out around us. Discover a place to settle, to sit a while. Sit. Feel this place come to us, slowly in wave after wave of subtle awareness - the crackling of dry leaves beneath us, the fluttering of pale leaves falling, the way they catch on their way down threads of stray sunlight here and there. Odd paths they make through the air, twirling, twisting, tumbling in arabesques in such silence in such long slow falls to earth. Slowly it comes to us in wave after wave of growing awareness. This is an opening too. Time loosens and slows now, perhaps because we are no longing moving, perhaps because it seems a place that is holding a slow sense of time to itself. Here, in this particular place in the woods, everything seems to come to rest in its own place around us - a place for every thing and every thing in its place - a kind of fullness, an arrival of a completeness. This makes it more than a fragment or shard of something larger. This place opens ourselves too, urging us to attend to here and now. It’s a long now (6).

Hear the too-wit of a bird, unseen. It is calling, or perhaps it’s just so delighted about something within its own self it has to send a song out.

LESSON #1: HOW TO LISTEN TO A BIRD SING

Take off all

your clothed and

clammy thoughts.

Sit awhile.

Make nothing up

between the intervals of silence,

but listen to them.

Between each breath

is a song you’ve forgotten,

is always calling us

to gather to this wild

and shocking world.

This music happens to us

before we can ever think about it

this song happens in us

before we can ever say it’s impossible

to listen before we speak

of nothing or everything.

Sit a while and gently reach out with eyes and ears and nose, to see and hear and smell more - the tang of Hemlock resin, the textured pattern of light and shadow of bark and leaf, the tangled lines of trunk, limb, branch and twig all drawn out and tending in long sinuous wanderings outward and finally upward. Notice that this is what turns this jumbled, snarled tangle of things into a meaningful pattern. This happens between us - leaf, twig, branch, or human, all searching, all urged through this tangle of life.

With the impress of this, take a deep slow breath now, settle once more on pelvis (7).

OUR BREATHS EACH TIME

Our breaths each time

reach out and come back.

They must so love the world

they always go back

for more.

Or perhaps I’ve gotten this

all wrong. This breath’s

not ours at all, but the world’s.

The world’s searching deep

into our opened chest

and then pulling back

for more.

This tide,

in its gravity of care

is drawing us on forever.

We open our eyes. Ask permission of this place to be here, not just in thought, but out loud, loud enough to feel its sound resonate in the chest. Say it with respect, as if meeting someone of importance for the very first time. This returns us to the conversation. Say “hello” to the ground we’ve already sat down upon, to the pale grey green ruffled lichen clasped to the side of a Red Oak, to the dangling Sassafras leaf turning orange upon the branch. Say “It’s nice to meet you” to the purple

Gentian pushing up through the leaf litter. Ask permission to be here with each of them. Now feel the body gradually relax - this is our reply (8).

There is a center to all this

and it’s all in its attraction

We sit a while longer, letting our eyes wander, following wherever they lead us. Patterns surface around us, then submerge one into another. The rough crusty edge of bark on a Shagbark Hickory leads us upward along its trunk to turn around a boll, twist into whirling grain toward its center. Spangled dots of soft yellow Hornbeam leaves drift through the airy understory and trace a dotted curve and dissolve beneath deep shadows under a Hemlock.

Notice how the patterns hold our attention, some more than others, and how they draw us into them. We feel drawn to these again and again, and as we are, we feel more and more relaxed (9). They attract us and become themselves centers of attention- and this too is a conversation. Here around this center of our being here, we discover other centers, the spirally grain on a tree boll, the unwrapping, rewrapping of purple Gentian petals, the star like clusters of tiny Asters up on the hillside. In offering our awareness to them, they have replied in offering some quality of themselves to us.

From high up in the canopy above us one Poplar leaf separates, descends and falls, like a stray thought gently into our lap. Held in our hand, its broad delicate sweep of pale yellow matches the breadth of our hand. Its creased veins reach out from midrib to margin alternating just like that of the tall tree itself. They crisscross those in our hand beneath.

See through the lamina of its gathered light, through its life lines of veins to our own beneath. The layers of life are permeable. One hand beneath another, both gathering one life through another, one life coming through another, lines of life cross. Along our mutual edge the margins crumble, the lingering light reveals that edge where one thing always becomes another is what we are here in relation to this edge of being. These layers come to us because we see them in ourselves.

Take slow deep breaths now and draw in the warm scents of mid day drying forest leaves. Realize that each scent we breathe in consists of a group of molecules sent to us from each particular living being that we are now physically absorbing into our bodies, and thus actually becoming part of us. Consider that every breath of air we breathe in has been breathed before, many, many times before - by that deer that paused before we came to the edge of the forest opening, by that Woodpecker, by that song bird singing too-wit, by that Poplar tree, even once long ago by Socrates, even before that by mastodons (10).

We close our eyes now, and in our mind smell those scents, see the colors, touch those textures, and follow those patterns and rhythms. Let them emerge and submerge one into another. Notice how they entwine with our thoughts, indeed become our thoughts just as those scents have become part of our bodies. Notice that that this is no longer a strange land, no longer a tangle, but now a familiar place of patterns we recognize. This is a conversation attracting us to what we share, what is living and wants to live within us, and us in them. This is a center and we are attracted to it (11).

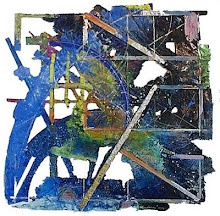

Open your eyes, but only softly. Reach for a pencil and notebook we’ve brought. Open it and begin to gently trace the patterns we’ve sensed and felt. This too becomes a conversation, like any genuine conversation in which we cannot know where it will lead us. We just join in. Notice now how we are following something, following toward something. Our lines echo one another over and over again, retracing, remembering one another, and another deeper pattern. We are drawing closer. And it pleases us!

We close our notebook, take a deep slow breath, and feel a fullness fill us. It feels whole. We respond by feeling whole ourselves. Standing up, we turn slowly around, scanning the immensity surrounding us. Notice those patterns and rhythms we drew from it all now looking back at us life familiar friends, smiling. No longer the maze we confronted when we entered the forest, it is now a labyrinth of meaning we’ve met (12). We remember David Waggoner’s poem “Lost”:

Stand still. The trees ahead and bushes beside you

Are not lost. Wherever you are is called Here,

And you must treat it as a powerful stranger,

Must ask permission to know it and be known.

The forest breathes. Listen. It answers,

I have made this place around you,

If you leave it you may come back again, saying Here.

No two trees are the same to Raven.

No two branches are the same to Wren.

If what a tree or a bush does is lost on you,

You are surely lost. Stand still. The forest knows

Where you are. You must let it find you.

We say “thank you” out loud, and begin slowly to amble back down the path we’ve come, refreshed.

* * *

We are all standing together on a branch of all life. This place, the Sun, moon, mountains, rivers, the leaves turning and falling in mid October, your breath, your reach and seeing - all are the drawing of being in and out, the art of what is. Long before our species was born, this drawing had been drawn. It is still being drawn. Each sunrise attests to it, each rustle of leaf, each breath of wind against our face. We live in it, each one of us, now. We can add to it, or we can try; we can also subtract from it. We are the only species given this two sided gift. We can chop it down, incinerate, strip mine, poison, and bury it like feces. But we don’t create it. We didn’t create it. If we destroy it, we can’t replace it. In a perverse imitation of God the creator of life, we have often become such un-creators.

Drawing, culture, pattern, these nutrient centers all about us, aren’t man-made. Even the culture of humans is not man-made; it is just the human part of the culture of the whole. We, and all we make of it are as much a part of nature as the Pacific or Atlantic Oceans (13).

When you look, and listen, think and speak directly and draw intently into and from this, something beautiful happens. This something is called art. If you think that way, speak and draw that way, this drawing then gets into your hand and heart. If people see and hear you, it gets into their eyes and ears, minds and hearts. But the art exists anyway. The only question is - are you going to take part in this great drawing song lifting over the mountain, out along the river, through the streaming night, in the teeming caverns of cities, and if so, how? (14)

FOOTNOTES:

1 Actually being in place is rare and not something we are familiar with to a large extent any more. Urbanized and industrially configured places have largely reshaped our relationship to place and thus to being there. Such places are shaped to their function, not for inhabiting them. Among the few left to us are places of religious worship, sports stadia, cemeteries, national monuments and parks. The rest have mostly become spaces of utility, of use, spaces in which things take place, not being.

*

2 Walking barefoot is one of those really simple things you can do to change your relationship to the land. Literally, you have to walk with respect - rocks and pebbles especially demand it of you.

*

3 An adelgid creature is moving south along the Appalachian chain and feeding on Hemlock, destined to kill them all and drastically change the ecology of riparian and riverine zones of life.

*

4 Sound helps create sense of place. The way it does is wonderfully evoked in The Last Quiet Place.

*

5 While we can refuse to see what’s right in front of us, we can’t refuse the sounds that come to us. The open space of woods might appear to be seen as out there, but the sound of it happens in our ears, within us, and we are made a little more vulnerable, a little more attentive to surprises.

*

6 In our own lines of daily passage, we move through many spaces, some have names, many do not. But some are places - this open space beneath towering trees we immediately recognize as a place especially its own in some way. It seems entire in some way. It seems whole. Here its dimensions unfolding in sight, scent and sound wrap around this place and belong to it. It is unmistakably alive, seamlessly in and of itself, way beyond ourselves and our human concerns. But this is important - this awareness of aliveness happens within ourselves. In this one moment we recognize it is some part of ourselves as well. In this moment we literally breathe it in with each breath. In this same moment a fissure rises too within us - how we are both part of all this and strangely separate, how this would not happen without our being here now along this path, how a part of ourselves would not arise to awareness without our being here. This rarely if ever is true at the office, the store, the expressway always on our way to some place else.

*

7 It can be difficult to give ourselves over to a place, to shake off self possession; we are so often turned back upon our separate selves, to live in our wandering minds and chatter to ourselves about how to make the world work for us. But slow, deep breaths can often return us to being in place.

*

8 This ritual of “talking to trees” can seem oddly uncomfortable, just as it does when we meet a stranger on the street unsure of their intentions, uncertain of what may come from the meeting. But out here in the woods no tree is going to assault you, even with an angry reproach. Asking permission out loud to be here as if everything here could hear it, moves our intentions from inside ourselves out into the world’s public space. It makes it public (and we feel it this way), makes it more real for this,and encourages our actions to follow our intentions . In doing this, we have subtly shifted our relationship to our surroundings from an I - It, toward the I - Thou relationship Martin Buber has written of. This changes how we see, smell, touch, and most importantly, how we know. For some of us, this can seem blasphemous in some vaguely uncomfortable way. It can conjure for us so called primitive people superstitiously believing they can actually speak to “spirits” in trees. We are not going that far here. We are just directly acknowledging our presence to other living creatures, and accepting the scientific fact that they too sense their environment and are capable of responding to it. They may not respond like a bird, or even by the snort of a startled deer, but they do in myriad ways carry on a conversation with other creatures in their surroundings. Just one of our own ways as humans is to speak.

*

10 There is a reason breath features so prominently in this walk in the woods. In a way “The air...is the soul of the visible landscape, the secret realm from whence all beings draw their nourishment. As the very mystery of the living present, it is the most intimate absence from whence the present presences, and thus a key to the forgotten presence of the earth,” and so offers us a direct path back into its presence. So David Abrams introduces us to the fascinating role air and breath plays in our awareness and in our cultural history.in his chapter “The Forgetting and Remembering of the Air,” in his The Spell of the Sensuous (1996)

*

11 There is a center to all this and we are attracted to it. With practice we can feel its pull growing in us. In their work, painters and drawers daily feel this pull of attraction between shapes and the spaces between them. They really couldn’t do without that perception - It’s what enables them to create meaningful relationships in their work.

*

The natural world, including our own inner nature, contains attractions, that hold it meaningfully together and sustain it in balance. We are drawn to these meanings, this balance. When we experience ourselves as being ‘in place’ When we actually notice what our seeing experience is like, we become aware that we are in the center of a pool that moves out all around us. There is no latitude and longitude, no intersection of streets, no house number to our location. This is a center of a field of experience. This is perhaps why when we meet something there is the experience that they have come to us - they have approached into our field of experience. For an artist, the spaces between are electrified and charged. When we experience a reciprocal meeting with something else in this concentric field around us, we realize that they too are at their own center of experience, and so when we meet our two centers interact, our fields overlap and a moire pattern is created. There is mutual attraction. In the natural world there is an especially charged attraction between these centers. Physics has come to know that this happens at all scales of existence, from the sub atomic to the planetary.

*

12 We have been taught that images are like pictures, either before us in the world or in our “mind’s eye.” But the images we experience are rarely static - they change as we experience them. It is much more accurate to say that we see/experience through images, and in this sense images are very much a medium we live within. And because images seemingly "out there" change us, warm red increasing our heart rate for example, images are an important intermediary between nature and ourselves.

*

13 “We, and all we make of it are as much a part of nature as the Pacific or Atlantic Oceans” seems a radical statement in our world and in our time. For much of our human history it was not. Our contemporary concepts of psychology are cleaved along the lines of Freud and Jung. Freud accepted that we are estranged from the world (note his Civilization and its Discontent), but Jung gave us the concept of psyche as not something hidden unconsciously inside our individual selves somewhere, but that it we with our conscious minds that are inside a psyche that is alive all around us in nature.

*

14 Some of the content, and many of the words in these last three paragraphs, are rudely and crudely appropriated and recast from Robert Bringhurst’s brilliant essay "Poetry and Thinking," in his The Tree of Meaning: Language, Mind and Ecology (2006), p. 143.

SOURCES FOR FINDING OUT MORE:

All I’ve described here might be subsumed under the concept of ‘embodied knowledge’ - that feeling, sense experience, proprioception and perception, are not just subjective, but part of the circuit of real meaning circulating through our embodied experience with the world. This runs counter to much of the mechanistic view of traditional psychology, art practice, science, and philosophy. But there is a growing body in all these fields that does reflect what shamen, poets and singers have always known. Here is a short list of sources that explore this current body of knowledge:

The practice of experience in nature:

Alexander, Christopher, “The Practical Matter of Forging a Living Center,” chapter 5, The Nature of Order: Book Four: The Luminous Ground, 2004, Center for Environmental Structure, Berkeley Calif.

Brown, Tom,

Tom Brown’s Field Guide to Nature Observation and Tracking, 1977

Hempton, Gordon,

One Square Inch of Silence, 2009

Macy, Joanna,

Coming Back to Life, 2013

Nicolaides, Kimon,

The Natural Way to Draw, 1941/1969

Rezendes, Paul, Tarcher, Jeremy,

The Wild Within, 1998,

Woodard, Honor, the photographic work (a contemporary artist working very deep into embodied knowledge, but whose work is largely unavailable except through web pages - see her personal blog

Silvermoonfrog for a taste).

The psychology of experience and consciousness entangled with nature:

Abrams, David,

The Spell of the Sensuous, 1996 and

Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology, 2010

Arnheim,

Visual Thinking, and

Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye, (1954)

Benediktsson and Lund,

Conversations with Landscape, 2010 (“

Introduction online”)

Gendlin, E.

Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning:A Philosophical and Psychological Approach to the Subjective, 1962

Nicholsen, Shierry We

ber,

The Love of Nature and the End of the World, 2002

Reed, Edward S.,

Encountering the World: Toward an Ecological Psychology, (1994)

Sewall, Laura,

Sight and Sensibility: the Ecopsychology of Perception, 1999

The science of the the entanglement of consciousness with nature:

Bateson, Gregory,

Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity, 1979

Bohm, David,

Wholeness and The Implicate Order, 1980

Edelman, G .

A Universe of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination, 2000

Gibson, James J.,

The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, 1986

Konner, Melvin,

The Tangled Wing: Biological Restraints on the Human Spirit, 2002

Margulis, Lynn,

What is Life? 1995, and

Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution, 2008

Maturana and Varela,

The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding (1998)

Maturana,

Autopoieses and Cognition: The Realization of the Living, 1980

Prigogine and Stengers,

Order Out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature: p. 83: "Nature must be described in such a way that man's very existence becomes understandable. Otherwise, and this is what happens in the mechanistic world view, the scientific description of nature will have its counterpart in man as an automaton endowed with a soul and thereby alien to nature."

Tucker, Don,

Mind from Body: Experience from Neural Structure, 2007

Varela, Francisco,

The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, 1993

The philosophy of the entanglement of consciousness with nature:

Bringhurst, Robert,

The Tree of Meaning: Language, Mind and Ecology, 2009

Cronin, William

Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, 1996

Dewey, John,

Experience and Nature, 1958 and

Art as Experience, 1934

Harding, Stephen,

Animate Earth, 2006

James, William,

The Principles of Psychology, (1850/1950)

Johnson, Mark,

The Meaning of the Body: Aesthetics of Human Understanding, 2007

Jung, C. G.,

The Earth Has a Soul: The Nature Writings of C.G. Jung, 2002, edited by Meredith Sabini,

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, “Eye and Mind” in

The Primacy of Perception, 1964, and

Phenomenology of Perception, 1962

Roszak, Theodore,

The Voice of the Earth: An Exploration of Ecopsychology,1992

Whitehead, A. N.,

Science and the Modern World, 1925 and

Process and Reality, 1929

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)