I have had difficulty getting caught up by these questions. I suppose my alienation from the issue (for that is what it feels like) stems from my own relationship to my materials - paint, canvas, pigment, brushes, oils, charcoal, clay, steel, paper, words, vowels, consonants, breath. I've never felt like I had to attain some kind of masterful control over a medium. After all, my materials are not just stuff lying around to breathe life into, but media - so already alive and resonating with the world. It's a dance I'm concerned to join, to connect to, to understand within, not a battle to win or an opponent to conquer. But of course the best craftsmen I've met understand this kind of partnership as well as I do. It's just not generally appreciated. Mastery is not the most important thing, either in art or craft - or life. But that's not generally appreciated either.

I do believe very much in craft. I'm not disparaging it. It is just that it is the craft of swimming, not hammering that I'm committed to.

I was once asked to write about the issues between craft and art. Here was my take on it then:

“Between Art & Craft”

Artpapers, December, 1992

(working in my studio in 1992)

"Craft is a matter of doing necessary things well. Unfortunately in our culture today, very little is clearly understood as necessary. What we are left with in both art and craft is personal necessity, and that is increasingly reduced to the manipulation of signs and symbols that are shorn of once vital connection to experience. Because of this reduction, all craft has become an anachronism.

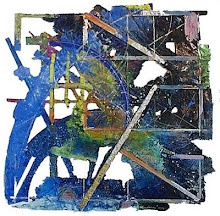

On the floor of my studio lie the scattered and scuffed up remains of paintings stillborn, bits and pieces that couldn’t move me or compel me to accept their necessity. they remain here because I’ve mostly, but not quite wholly, given up on them. Some of these pieces remain, like such remnants always do in artists’ studios, as keepsakes; but others because I might one day be astute enough, or even just plain lucky enough, to find the bit that’s necessary in them. Even though they constitute a pile of rubble now, grown old over the seventeen years I’ve spent in this particular studio, I am afraid to throw it all away. It is a midden heap of my failures, which may yet be redeemed.

It is by such scraps that I build my paintings. These scraps are torn bits and pieces, never wholes, and in a sense I never craft my paintings, only find them. There is some magic in this, and on the rarest of occasions, even grace.

("Moonlight Over Howgill Farm," 1999, mixed media)

This has come to seem necessary, but never wished for. Most of my paintings confirm that scraps are all I have, bits and pieces of consciousness of world and self. It seems a small orbit for painting or myself. I know I’m not alone in this predicament. Artists of all kinds have never before found it so difficult to transform experience into a generally understood and coherent language. As a result it is our individual isolation that more and more defines us as artists, as it does ourselves as individuals. There seems hardly any practical need for craft when we have only our individual selves to save or glorify.

On a studio table strewn with drawings, there is a ceramic bean pot. Made in Jugtown, North Carolina almost sixty years ago, it is rich in age, use, and craft. Its glaze is crackled and fissured, darkened by cooking along the bottom and part way up the sides to a deep black. On both sides the handles are pinched into the body with the fingerprints of the potter plainly visible. From the moment this pot was sliced wet from the potter’s wheel it has bulged with a fullness and wholeness. Still after all these years it always looks full, though no one in years has been really tempted to fill it with beans and put it in the oven. Its aesthetic is that welded to its original everyday purpose.

("Jugtown Bean Pot," circa 1930's, Ben Owen, Jugtown, N.C.)

On most days, no matter how many finished paintings lean against the studio wall, the empty pot is the most whole thing here. It’s hard to match its sense of necessity, in reasonableness or practicality, or in a kind of truth that doesn’t stray far from these sources. This pot is fully turned from its culture. But that culture is gone now. The pot speaks of a world gone under, where the relationship to things was different, and was necessarily more intimate, magical, and marked with clearer limits.

But here in my studio, what is clearly necessary? Generically speaking, paintings seem quite unnecessary. Here surrounded by jars of wonderfully exuberant colors, sheets of rich cream tinted paper, soft as skin, anything seems possible. But what seems necessary on most days is just the pressing need to make paintings; on the very best of them to get something right and thereby draw some private truth from it, and on the worst of them to simply make some contact with the world. These seem today matters of only the most personal and private necessity.

It is commonplace for artist like myself to simply dismiss the crafts as primitive formative versions of the fine thing art has become. When someone points to a work of craft on the “cutting edge” we know they are talking of its artfulness and not its craftsmanship. Despite two heroic efforts in modern times, the Arts and Crafts Movement and the Bauhaus, it is still perceived as a regressive rural phenomenon in a progressive urban culture. Craft criticism is largely an addendum to art criticism, left to languish or fit itself to the current fine art paradigms; which is to say we simply can no longer summon a need for craft any more than we can for much of our past. What little we keep is with nostalgia, and that is the place craft largely has for us today. But I believe craft is essential. Disparaged, sentimentalized, even transformed into “fine craft,” craft is still a matter of doing necessary things well. In a culture where nothing but money is really considered necessary (that is, where all values come down finally to a price), it may be impossible to define such a concept of craft without falling victim to nostalgia, or trying to reshape it one more time. The necessity to form a shape in a certain traditional ways has become largely a mystery to us today. What we are left with in both art and craft is only a personal necessity to require that real life be the private life and and not the life of the community.

There is a connection between our entrenched notions that the personal is somehow, however impossibly, the real authentic form of cultural life, that our past is behind us, and that craft is out of place, a footnote to other pressing cultural forces. Craft is inseparable from traditional cultures. Thus the crafts are permanently estranged today from their sources. Such traditional communities are marked by the continuity they weave between individual and community, past and present. For such societies the past is not dead, not even past, but living all about, transformed into a timeless nurturing presence, and the individual is not isolated, but part of a seamless coherence. In that social reality - and it is quite different from our own - the important issues always remain the same, whether practical concerns for the shape and form of a cup, or metaphysical models for the cosmos. So what is valuable about craft is valuable about the community and the past, and the future. These values are not ideals, but hard truths derived from living within the limits of the natural world. It is these practical aspects that have borne and sustained crafts.

And it is to these aspects that artists can no longer clearly turn for a grounding in the practice of the necessary. I do not mean to the slickness, cuteness, prettiness, or comeliness that often pervade the crafts as well as fine arts, but to a standard of quality stubbornly grafted to the object created. This is a kind of attention and concentration inhering in the practical task at hand of creating something plainly necessary for one’s own immediate life and community, but which nevertheless connects the fullness of a bean pot to a past far older, and to an inconceivable future."

The issue won't go away of course, no matter what I say. On last Sunday, with friends over to celebrate July 4th, and some of us drifting into the studio, an old friend (and collector of my work) pointed to some older paintings stacked against the wall and said "I'm glad to see you're doing that kind of work again - they're more crafted. You can see it took the artist a long time to do it. People appreciate that." And so they do!

In 2003 I saw Jason Perry's punk pots at the Tate in London. He was that year's winner of the Turner Prize. He exemplifies the conundrum of art and craft for me, and bridges that dichotomy. I love his work. I also loved the Chapman Brothers political drawings in the adjoining room. They were the runners up for the prize. They displayed about 100 small framed Goya etchings...the real things...that they painted black and white cartoon heads upon. This might be thought of as a sacrilegious desecration, but for me they were gorgeous new works of art. What I'm saying here is that we don't need to worry about the difference between art and craft. Real artists are blasting through those terms and redefining ideas of what is printmaking or painting or ceramics. The solid confidence of that bean pot makes me feel protected and safe in a world of trendiness and devotion to money. I don't see it as craft...just an old friend, talking about his life...like what Jason Perry is doing and the Chapmans.

ReplyDelete