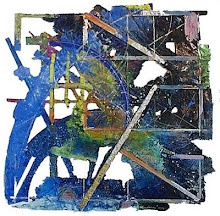

Two works from the Beowulf Cycle:

"So Grendal Ruled in Defiance (2002) charcoal on paper":

"Wall Stead - In Heorot" (2010), oil on paper 12"h. x 30"w.:

A new friend wrote me saying these works reminded him of Rothko and Mondrian. Certainly. But I was hunting after something grimmer, with the teeth of wild dogs in the night - something in the silence after you hear the howling stop at midnight up on the ridge above my house; something old, very old, yet something still with us.

After all, this cycle of works was born out of that long time after September 11, 2001 when we all struggled with what terror means in our lives, some of us for the first time. The television repeated a thousand times over the long shot clips up the Manhattan canyons of the falling towers and the close up shots of frightened people fleeing wearing cloaks of the ashes of thousands of others. But the t.v. was impotent to tell of what it meant. That we each had to do ourselves. And we had to do this midst a storm of words generated by the media afterward, including the absurdity of our President exhorting us to just go out and fly and buy!

We don't see those t.v. clips much any more of course - that sense of horror can't be maintained. Through repetition we became numbed, but the sense of it drives deep within us into subterranean rivers. There it flows with our deepest fears and desires. Only later does it push up in new springs to the surface, where we drink of it in the form of revenge or hate, distrust, shame, alienation, estrangement and disaffection.

In the hollowed out days following the terrorist attack, I too struggled with some way to understand what had happened, and what, in its aftermath, was happening to my country. Of course, I went to the studio, picked up the deepest black stick of charcoal I could find, and began to draw.

A month and a half later my sister gave me a new translation of the 8th Century Anglo Saxon poem Beowulf by the Irish poet Seamus Heaney. It stunned me. Here was a clear sense of where to take this work: the starkly hewn way it carves and holds in constant balance line by line a palpable sense of light and dark, beginnings and ends, the ephemeral interlacing of humankind and nature, the way a line welds together a descriptive fact about nature with an evocation of human emotion, the way this energy is coiled and then released through succeeding lines like a driving wave. All these qualities resonated with my own confusion about what 9/11 meant, and suggested a "holding form" - that embryonic bud of a visual vocabulary, with which to explore toward some understanding.

It's now been over 8 years since that Tuesday morning in September. Some of us would like to forget. Some of us can't. As a country we are still trying to come to grips with what the presence of terror means in our lives. Our civic leaders have tried to turn it into a war - that way it is so much more understandable to a country gotten used to one war after another (after all, in my 65 years there have only been 10 when my country was not at war!). Our conflicts can't so easily be encapsulated I think except within the hollow pretense of newspapers, t.v., or on political stumps. The sources for our "wars" run fearfully deep within us - the Beowulf saga is a clear testament to that. We are at "war" with deep conflicts within ourselves, and we extend them not only to each other but to the natural world itself. It sometimes seems we are at war with the world at large, and the wall steads we have built to stand against disaster are falling all about us, like the mead hall in Beowulf's Heorot.

It's an old plaint and lamentation - the destruction of the world as we've known it. And in its destruction, the creation of something new.

Today I'm still exploring this work, still exploring my understanding of what it means through the work itself. It is called The Beowulf Cycle, and if you would like to see more examples just click here .

Monday, March 29, 2010

Friday, March 12, 2010

The Figure of a Face that a Painting Makes

The poet Robert Frost wrote:

"Abstraction is an old story with the philosophers, but it has been like a new toy in the hands of the artists of our day. Why can't we have any one quality of poetry we choose by itself? We can have in thought. Then it will go hard if we can't in practice. Our lives for it.

Granted no one but a humanist much cares how sound a poem is if it is only a sound. The sound is the gold in the ore. Then we will have the sound out alone and dispense with the inessential. We do till we make the discovery that the object in writing poetry is to make all poems sound as different as possible from each other, and the resources for that of vowels, consonants, punctuation, syntax, words, sentences, metre are not enough. We need the help of context- meaning-subject matter." "The Figure a Poem Makes" (1939)

Yes, abstraction is a very old story - the story of the long search for some certainty as pure and unassailable as a prime number - often a search for transcendence over a tumbling, troubling world than for something immanent and essential at the root.

Poems have the benefit of sounds to send them beyond abstraction out into the heard world, but paintings have bodies to send them out beyond just thoughts or ideas.

Paintings confront us - like a figure of a person might who stands before us.

He or she stands there in front of us in order for us to meet, to encounter one another - together. The painting not only presents a representation and makes a "figuration," but presents a presence to us. We don't, right there and then, need to call for the help of context (drawing subject matter from outside that circle). It's already there. It's inherent in the very context of the meeting. We have brought it to the meeting and it comes flowing to us, and surrounds us. It's there between us. No different than all the meetings we attend, either in our dream or daylight hours. All are hours chambered with such echoing resonance. Which is why a sage could say "The world is not happening to you -you are happening to the world."

Poems have the benefit of sounds to send them beyond abstraction out into the heard world, but paintings have bodies to send them out beyond just thoughts or ideas.

Paintings confront us - like a figure of a person might who stands before us.

He or she stands there in front of us in order for us to meet, to encounter one another - together. The painting not only presents a representation and makes a "figuration," but presents a presence to us. We don't, right there and then, need to call for the help of context (drawing subject matter from outside that circle). It's already there. It's inherent in the very context of the meeting. We have brought it to the meeting and it comes flowing to us, and surrounds us. It's there between us. No different than all the meetings we attend, either in our dream or daylight hours. All are hours chambered with such echoing resonance. Which is why a sage could say "The world is not happening to you -you are happening to the world."

Waking each morning we wake into conversation with the world. We ask - world! what today do you have to offer us? What dangers do you present us with today? World! - what do I have to offer you today? World - how will we get along this day?

So it is with paintings. Well, yes - so it is too with everything we meet each day - all the objects, all the surfaces, all the aromas and sounds we encounter. It's all too much to fully take in, so we filter much out. We choose what to gather in and what to shut out, and as we do, we collect and thus construct what the world amounts to for us, limited enough to comprehend, bounded enough to be certain enough.

But so it is with most things. As James Hillman writes:

“All things show faces, the world is not only a coded signature to be read for meaning, but a physiognomy to be faced. As expressive forms, things speak; they show the shape they are in. They announce themselves, bear witness to their presence: “Look, here we are.” They regard us beyond how we may regard them, our perspectives, what we intend with them, and how we dispose of them. This imaginative claim on attention bespeaks a world ensouled. More - our imaginative recognition, the childlike act of imagining the world, animates the world and returns it to soul.” A Blue Fire, “Nature Alive,” p. 99:

Or as I say in a poem:

FACES

All things show their faces when we do.

All things speak when we do.

The first face, the first word,

they blossom into all the others.

They all are true.

They say 'seeing is believing." It means many things, but is repeated so often to reinforce just one central point - the empirical one - the efficacy of practical experience unblurred by affect. But the reality remains that 'believing is seeing' is also just as much a part of our actual daily experience, and part of how we experience the world. It recognizes that we insert ourselves into the world with our thoughts, our dreams, our actions, even our imaginings.And it may be just as true that the world inserts herself into ourselves with her own thoughts, dreams, actions, and imaginings.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)